Recursive Algorithms

#algorithm #computer-science Sometimes we design an algorithm to solve a problem by solving a smaller instance of the same problem, unless the problem is so small that we can just solve it directly. We call this technique recursion.

Factorial of a number

The factorial of a number can be calculated using a for loop, but it can also be considered as $n! = n \cdot (n - 1)!$. Therefore, to calculate $n!$ it is sufficient to calculate $(n - 1)!$ and to calculate $(n - 1)! = (n - 1) \cdot (n - 2)!$ you only need to calculate $(n - 2)!$ and so on. Below is a Python implementation of this algorithm.

```python fold title:factorial

def factorial(n):

if n == 0:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial(n-1)

>[!note] Note

>The idea of recursion has two simple rules:

>1. Each recursive call should be on a smaller instance of the same problem, that is, a smaller subproblem.

>2. The recursive calls must eventually reach a base case, which is solved without further recursion.

# Palindromes

In another example, we could view checking if a word is a palindrome as a recursive problem. Here are the basic rules and base cases:

- If the string is made of no letters or just one letter, then it is a palindrome.

- Otherwise, compare the first and last letters of the string.

- If the first and last letters differ, then the string is not a palindrome.

- Otherwise, the first and last letters are the same. Strip them from the string, and determine whether the string that remains is a palindrome.

Below is a Python implementation of a function that decides whether the input string is a palindrome or not.

```python fold title:palindrome

def is_palindrome(s: str) -> bool:

s = ''.join(c.lower() for c in s if c.isalpha())

if len(s) <= 1:

return True

if s[0] != s[-1]:

return False

return is_palindrome(s[1:-1])

The Power Function

We can also write a function for calculating integer powers of a number. Here is the general sketch:

- The base case is when $n = 0$, and $x^0 = 1$.

- If $n$ is positive and even, recursively compute $y = x^{n/2}$, and then $x^n = y \cdot y$.

- If $n$ is positive and odd, recursively compute $x^{n-1}$, so that the exponent either is 0 or is positive and even. Then, $x^n = x^{n-1} \cdot x$.

- If $n$ is negative, recursively compute $x^{-n}$, so that the exponent becomes positive. Then, $x^n = 1 / x^{-n}$.

Below is a Python implementation of this algorithm.

python fold title:'power function' def int_pow(x, n): if n == 0: return 1 elif n > 0: if n % 2 == 0: y = int_pow(x, n // 2) return y * y else: return int_pow(x, n - 1) * x else: return 1 / int_pow(x, -n)

Memoization

When using recursive functions, a lot of the times there are calls to the function more than actually needed. This could result in the program to be inefficient. We can use a technique called memoization to save the computer time when making identical function calls. Memoization, as a form of caching, remembers the result of a function call with particular inputs in a lookup table, called the memo, and returns that result when the function is called again with the same inputs. Memoization makes a trade-off between time and space. As long as the lookup is efficient and the function is called repeatedly, the computer can save time at the cost of using memory to store the memo. A simple case of recursive algorithms where memoization can help is generating Fibonacci numbers. Below is a Python implementation of this algorithm. ```python fold title:”Fibonacci with memoization” def fibonacci(n, memo=None): if memo is None: memo = {} if n <= 1: return n if n in memo: return memo[n] memo[n] = fibonacci(n - 1, memo) + fibonacci(n - 2, memo) return memo[n]

# Bottom-up

Sometimes the best way to improve the efficiency of a recursive algorithm is to not use recursion at all!

A simple case of recursive algorithms is generating Fibonacci numbers. However, an iterative technique called the _**bottom-up approach**_ can save us both time and space. When using a bottom-up approach, the computer solves the sub-problems first and uses the partial results to arrive at the final result.

For example, in the case of generating the Fibonacci numbers, the bottom-up approach algorithm works like this:

- If $n$ is 0 or 1, return $n$

- Otherwise,

- Create variable $\text{twoBehind}$ to remember the result of $n - 2$ and initialize to $0$.

- Create variable $\text{oneBehind}$ to remember the result of $n - 1$ and initialize to $1$.

- Create variable $\text{result}$ to store the final result and initialize to $0$.

- Repeat $n - 1$ times:

- Update $\text{result}$ to the sum of $\text{twoBehind}$ plus $\text{oneBehind}$

- Update $\text{twoBehind}$ to store the current value of $\text{oneBehind}$

- Update $\text{oneBehind}$ to store the current value of $\text{result}$

- Return $\text{result}$

This approach never makes a recursive call; it instead uses iteration to sum up the partial results and calculate the number. The bottom-up algorithm has the same $O(n)$ time complexity as the memoized algorithm but it requires just $O(1)$ space since it only remembers three numbers at a time.

Here is a Python implementation of the bottom-up approach for the Fibonacci problem:

```python fold title:'Fibonacci bottom-up'

def fibonacci_bottom_up(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

twoBehind = 0

oneBehind = 1

result = 0

for _ in range(n - 1):

result = twoBehind + oneBehind

twoBehind = oneBehind

oneBehind = result

return result

Dynamic Programming

Memoization and bottom-up are both techniques from dynamic programming, a problem-solving strategy used in mathematics and computer science. Dynamic programming can be used when a problem has optimal substructure and overlapping subproblems. Optimal substructure means that the optimal solution to the problem can be created from optimal solutions of its subproblems. Overlapping subproblems happen whenever a subproblem is solved multiple times.

Towers of Hanoi

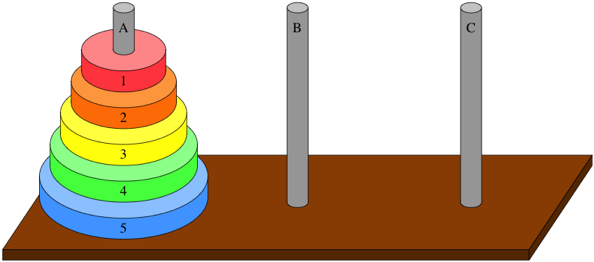

Towers of Hanoi is a classic example of recursive algorithms.

You are given a set of three pegs and $n$ disks, with each disk a different size. Let’s name the pegs A, B, and C, and let’s number the disks from $1$, the smallest disk, to $n$, the largest disk. At the beginning, all $n$ disks are on peg A, in order of decreasing size from bottom to top. The goal is to move all $n$ disks from peg A to peg B. Here is what the problem looks like for $n = 5$:

To solve the problem, we first start with the base case. This is easy. When $n = 1$, we should just move $1$ disk from peg A to peg B. Moving a single disk between any two pegs is very basic. For the case of $n = 2$, we can first move disk $1$ to peg C. Then we can move disk $2$ to peg B. Finally we move disk $1$ from peg C to peg B. The whole process takes $3$ steps.

For the case of $n = 3$, we can first move disks $1$ and $2$ to peg C. Note that we had previously shown that moving two disks from any peg to any peg is feasible. Now we just move disk $3$ to peg B and move disks $1$ and $2$ to peg B, using the three steps like before. So three disks can be transferred from any peg to any peg. The total prcoess for $n = 3$ takes $7$ steps.

In general, the process takes $2^n - 1$ steps for $n$ disks.

To solve the problem, we first start with the base case. This is easy. When $n = 1$, we should just move $1$ disk from peg A to peg B. Moving a single disk between any two pegs is very basic. For the case of $n = 2$, we can first move disk $1$ to peg C. Then we can move disk $2$ to peg B. Finally we move disk $1$ from peg C to peg B. The whole process takes $3$ steps.

For the case of $n = 3$, we can first move disks $1$ and $2$ to peg C. Note that we had previously shown that moving two disks from any peg to any peg is feasible. Now we just move disk $3$ to peg B and move disks $1$ and $2$ to peg B, using the three steps like before. So three disks can be transferred from any peg to any peg. The total prcoess for $n = 3$ takes $7$ steps.

In general, the process takes $2^n - 1$ steps for $n$ disks.

Continue learning about algorithms by reading about divide and conquer algorithms, binary search or insertion sort.

Sources:

- Khan Academy Recursive Algorithms and Towers of Hanoi